Drawing Exercises, Theory, and Practice

Some thoughts about drawing exercises: in my opinion the best ones are those which you devise for yourself, or adapt from existing ones, or even follow verbatim, with no changes, IF you first see precisely the reason to do them. If you do them from understanding, that sort of exercise will have the most meaning to you, and hence the best results. However, if you do an exercise “by rote”, as an unthinking follower, as if repeating a magic saying that will automatically generate a result, then…there probably will be little obvious result.

Some thoughts about drawing exercises: in my opinion the best ones are those which you devise for yourself, or adapt from existing ones, or even follow verbatim, with no changes, IF you first see precisely the reason to do them. If you do them from understanding, that sort of exercise will have the most meaning to you, and hence the best results. However, if you do an exercise “by rote”, as an unthinking follower, as if repeating a magic saying that will automatically generate a result, then…there probably will be little obvious result.What do I mean by “drawing exercises”? Simply put, they are any drawings done for the sake of learning rather than for expression or communication or creating a final piece of artwork. This might include life drawings, drawings of models of any kind, drawing from photos, sketching in a public place, experimenting with media of various kinds, the notorious “contour line drawings” and “color charts” art schools are so fond of, and many, many possible others.

It’s next to useless to do any drawing exercise out of a “sense of duty”, like dutifully taking medicine, or food for that matter, which you find detestable in flavour but which you think might be good for you. That’s starting with the wrong attitude and from the wrong place. Yet, inexplicably, people sometimes do life drawing in this way, by rote, as if the mere amassing of drawings would make any ultimate difference. Better to find an exercise which you enjoy, which you can do enthusiastically and out of love. Then it will not seem like drudge-work but be pleasurable. That exercise can then serve as a “beachhead”… a small piece of territory which you have acquired and genuinely made your own, from which you can gradually expand outwards and conquer more land.

If you are involved in the devising of your own art-experiments, you will naturally be tremendously interested in their outcome! Then, the results will stay in your memory, and affect your artwork for the better. Conversely, if you do an experiment or exercise “because you are told to”, because “the book said to”, ie artificially, because you “think you should for your own betterment and because _____________[insert name of favourite artist] always does it”, or “because the teacher assigned it” (as in, “I only draw in my sketchbook because teacher told us that in order to graduate we have to do three drawings a day in our sketchbook”), then you probably don’t understand why you’re doing it and thus will get little out of it. You are in a follower-copyist kind of mentality, not that of free-drawing entrepreneurial explorer of new lands. And if you are the sort of person who likes to buy and read a lot of art theory books, you even stand in danger of perhaps becoming “ a drawing theoretician”.

What is “ a drawing theoretician”? It’s a person who knows all the theory inside out, in terms of being able to expertly relate it verbally, reciting it chapter and verse, but can’t actually put it into practice. So, for example, this makes it possible for an artist to be able to relate all about “tangents”, but still have tangents everywhere in their artwork!

Or another example: years ago I had an assistant. He read my notes and bits and pieces of some of the other art theory books I had around the studio. Soon enough he could speak the lingo perfectly: always on about “VPs” (vanishing points) and “HLs” (horizon lines) and so on. But to look at his drawings, nothing had really changed: his understanding of and execution of perspective was no different, which was to say, perspective was more or less nonexistent in his drawings. So what was the point of having a bunch of fancy words circulating around his noggin? They weren’t connected to understanding. Why? Because he practiced very little: he rarely put pencil to paper to put these theories into practice, test them out, and make them his own.

Some artists I have met, noticing this “drawing theoretician” phenomenon, unfortunately then reject all theory and shy away from it compulsively, fearing that they will become a dreaded “drawing theoretician”, as if regular contact with drawing theory would result in the contraction of this terrible disease. This seems to me like throwing out the baby with the bathwater and shortchanging oneself, to mix my metaphors; and also sounds suspiciously like an excuse for not activating the intellectual side of one’s faculties. Perhaps too many artists had bad experiences in grade 9 being forced to study algebra or who knows what, and this talk of “drawing theory” sounds like a similar torture. So they avoid it altogether.

To avoid this danger, if you read a lot of theory or devise many of your own, you have to also practice drawing relentlessly. This unearths so many new questions and illuminates the theories so well, that they then become internalized, they are made your own, not just something that was read in a book or copied. If you have theories and try them out on the test-bed of your own artwork, you will soon see which are true and which false, and then revise them accordingly.

Another danger of studying theory: self-paralysis. Instead of being a doorway which opens new possibilities, too much immersion in theory may paralyze one with confusion and self-sabotage, often because the intellectual side of one’s brain is watching and critiquing before, during, and after one draws. Again, to forestall this happening, all you have to do is draw constantly as you study theory, alternating one with the other, and trying to keep each in its own compartment, or at least, keep each one on its own separate leash. So, for example, you may draw fast and intuitively, from emotion, without analyzing; and only afterwards, or upon a later viewing of your art, put on a quite separate hat and analyze, from theory and feel, what is working and what isn’t.

With practice, you can keep the compartments separate, and even during a drawing look at it from the theoretical-analytical viewpoint, making suggestions to yourself, without totally discouraging yourself and bogging down and losing spontaneity.

I should mention too that there’s an opposite danger to “the drawing theoretician”, and that’s what you could call “the over-practicer”. These individuals shy away from theory, but have a dogged but misguided belief that sheer volume of compulsive practice alone-without any reflection or theory mixed in-will surely lead to great progress. From time to time one can glimpse such types in life drawing classes; often they have mountainous piles of large swoopy charcoal drawings, and have many years of them back home. They are experts at practicing and practicing and producing that certain type of drawing, which seemingly becomes an end in itself. Sometimes these drawings are pretty nice, too. But then if you ask them to draw a comprehensible figure out of their head, without any reference, they cannot really do it. To me that shows a great disconnect: lots of practice, lots of raw data has flowed through their eyes and hands, but since it wasn’t connected to enough theory, their minds didn’t catch and hold it; they didn’t store enough of that raw information, haven’t internalized it, and hence can’t access it and make use of it creatively, for their own purposes.

The best theory and theoretical understanding evolves out of practice, and vice-versa. In the world of science, for example in the testing of jet planes, the theory was and is tested in practice, the results of which successively modify the theory, until a harmonious and effective balance is arrived at. So it can be for the artist: theory and practice held in balance, each augmenting the other.

But in no case can theory ever be “ a successful drawing generator”; knowledge of theory alone guarantees nothing. The gladiator-arena that is the creation of new each drawing is still the important thing, and once the doors of that arena close behind you and you step forwards into the field to do battle, you are on your own...and that’s the fun of it!

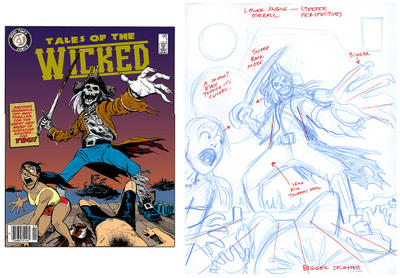

*PS: The image accompanying this post? Just a strange drawing from an old sketchbook…I think I was enjoying a certain brand of marker I’d just bought…