Object-Tracing

Every artist has heard of tracing: tracing a photo, or perhaps tracing another artist’s work, for learning’s sake---or worse, for theft. But, here’s another fun kind of tracing that comes in handy from time to time: what I call “Object-Tracing”.

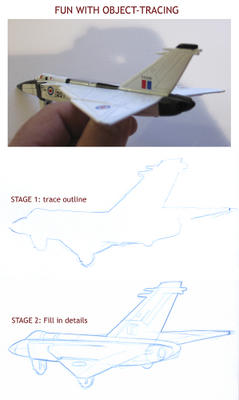

Every artist has heard of tracing: tracing a photo, or perhaps tracing another artist’s work, for learning’s sake---or worse, for theft. But, here’s another fun kind of tracing that comes in handy from time to time: what I call “Object-Tracing”.Object-tracing is simply that: tracing any small object which is of manageable size. You choose any point of view you care to, orienting the object at whatever angle you wish, then sticking to it. As shown in the image, you hold the object in one hand, while tracing its rough outline on the piece of paper beneath. To ensure steadiness, the object can be rested on the paper. Obviously, you can’t move the object, or your head, while tracing the outline! If you do, it won’t work because the outline will not be consistently from one view. Also, it helps to close one eye, because if you are close to the object the stereo view from your two eyes can make it harder to determine the exact outline.

Once you have a rough outline, it’s usually fairly easy to fill in the rest of the drawing by eye, following the indications suggested by the silhouette.

Why do this? Well, I started doing it as a time-saver, back before digital cameras were readily available. It was a quick way, especially in advertising work where the deadlines are extremely short, to get an accurate drawing of an object in perspective, when a photo from the specific angle desired was not available. So, for example, I’d use this technique to draw a tilted steep-angle perspective shot of a beer bottle in this way, or a model car, or a skull model I have on my shelf. Other examples include drawing a cell phone, a small porcelain coffee cup, and small pair of scissors. Any small object that can be easily handled can be traced in this way.

As I said I started doing this out of sheer expediency, to make the deadline and get an accurate-looking product shot for an ad rendering. But I soon noticed something interesting: that it was a tremendous way to observe silhouettes, to learn about their exact nuances. Of course later, in cartooning, you may change and exaggerate some elements of the “true” silhouette for artistic purposes, to make the outline communicate better; but that was not the point. By doing object-tracing, I found I was forced to carefully study and record the exact outline of an object, not what I imagined it to be, which was often the case when setting an object up and drawing it by sight, not tracing it. In the interval between observing an object or model, and then moving hand to paper and putting down a line, the mind and imagination and habit could easily alter things, so I was setting down on paper not exactly what was there, but what was imagined or altered by imagination.

Object-tracing on the other hand, as dull and non-artistic as it is in a certain way, removed this interval, and thus removed any personal distortion from the process (again, though, you can’t move head or hand-and-object, or the results won’t be accurate at all. With a bit of practice you get good at it.) In this way I accidentally discovered that it was a great way to study silhouettes, because you are forced to draw only the silhouette: the object blocks the rest, so you can’t draw inside the form until the object is removed.

In turning a small object such as a toy car, drawing it from many angles, drawing it from closer and from further, you can discover for yourself many small facts about perspective and perspective distortion. In a way this can “bring alive” many things in perspective and the study of the silhouette which, when written in an art book, can sound kind of dull and boring. You can even start by tracing a cube, thus learning the true angles of a cube as it turns in space, committing these angle to memory.

A couple of small notes: of course this is the same as projecting the silhouette of an object onto a wall with a bright light, but that method enlarges the outline to such a great extent that it is difficult to trace. The beauty of this method is you can do it quickly and quietly, without equipment. Secondly, even though digital cameras now are readily available, to the student or artist who wishes to study the silhouette, this method is far more instructive (not to mention, still quicker) than shooting and printing out and then tracing a digital image of an object.